Established back in 1570, Vilnius University Library has many unique collections in its rich stores. Among the most significant ones is a collection of old cartography, rare books and documents gathered by the historian Joachim Lelewel (1786–1861). The distinguished historian, bibliologist, numismatist and professor of Vilnius University bequeathed his personal collection to Vilnius University Library.

Established back in 1570, Vilnius University Library has many unique collections in its rich stores. Among the most significant ones is a collection of old cartography, rare books and documents gathered by the historian Joachim Lelewel (1786–1861). The distinguished historian, bibliologist, numismatist and professor of Vilnius University bequeathed his personal collection to Vilnius University Library.

Joachim Lelewel was a scholar of a worldwide renown. His contributions to historical geography, numismatics, bibliology and other areas of science are analysed by researchers of various countries. Joachim Lelewel delivered lectures at Vilnius University 1815 through 1818 and 1822 through 1824. He was very popular among students and his lectures were crowded with listeners. His innovative approach, criticism towards reputable works of Polish and Russian historians and his rebellion against authorities captured the attention of both students and the Tsarist Russian authorities. Due to a court case of Philomaths and Philarets, he was forced to leave the university. After that he lived in Warsaw, Paris and Brussels, but Lelewel never forgot Vilnius. The greatest passion of the professor was collecting of cartography.

Illustration:

Joachim Lelewel’s set of colours (pigments) (19th century).

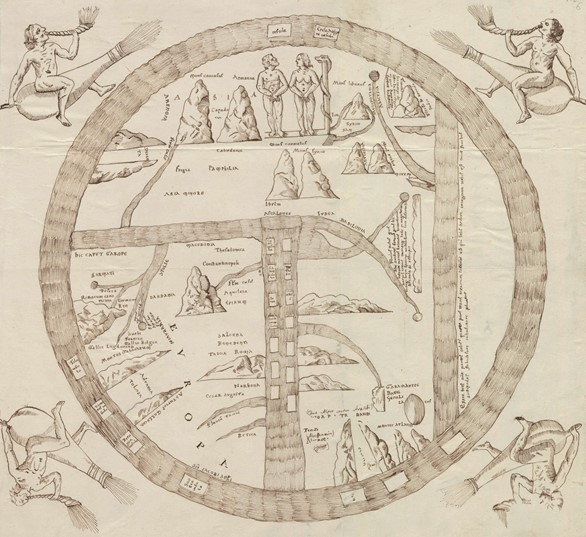

Map of the world. Manuscript copy by Joachim Lelewel (19th century). Original copy (12th century) is kept at Turin National University Library. From Imagines Mundi, a notebook with 43 manuscript maps by Lelewel >>

Joachim Lelewel’s personal collection of old cartography is a core element of the library’s cartography collection, the richest in Lithuania and one of the most interesting in Eastern Europe. Joachim Lelewel’s collection contains atlases by Ptolemy, Gerardus Mercator and Jodocus Hondius and many such masterpieces. Lelewel’s collection makes up 70 per cent of the old atlases collection of Vilnius University Library.

Beatus of Liébana was a Spanish monk, who in the second half of the 8th century wrote a twelve-volume work called Commentary on the Apocalypse. Beatus laboured on his Commentary in the belief that the world would end in the year 800. Though the prophecy was not fulfilled neither in the 9th, nor in the following centuries, the monk’s manuscript continued to be held in high esteem and many copies of his text were produced in the medieval monastery scriptoriums. In the upper part, the round world map, which is depicted in the manuscript copies of Beatus – a so-called Mappa Mundi – portrays the first people, Adam and Eve, in Eden. The round map shows the then-known parts of the world – Asia, Europe and Africa. In accordance with Pliny’s worldview, Beatus left some space on the right side of the map for the fourth, a yet undiscovered and only conjectured region of the world. This early image of the world is oriented differently than it is usual today – the upper part of the map shows the East and not the North as it is customary.

Beatus’ manuscript has not survived and only copies of it have reached the present day. One version of this so-called Beatus’ map was copied by Joachim Lelewel in the 19th century. Lelewel’s manuscript map – a copy of a copy – depicts a 12th century document kept at Turin National University Library.

Old Astronomical Observatory of Vilnius University. Marceli Januszewicz’s watercolour, 1836.

The professor lived in the apartment which was situated in the central campus of the university. Students that wished to chat, discuss or consult with the professor would often gather there.

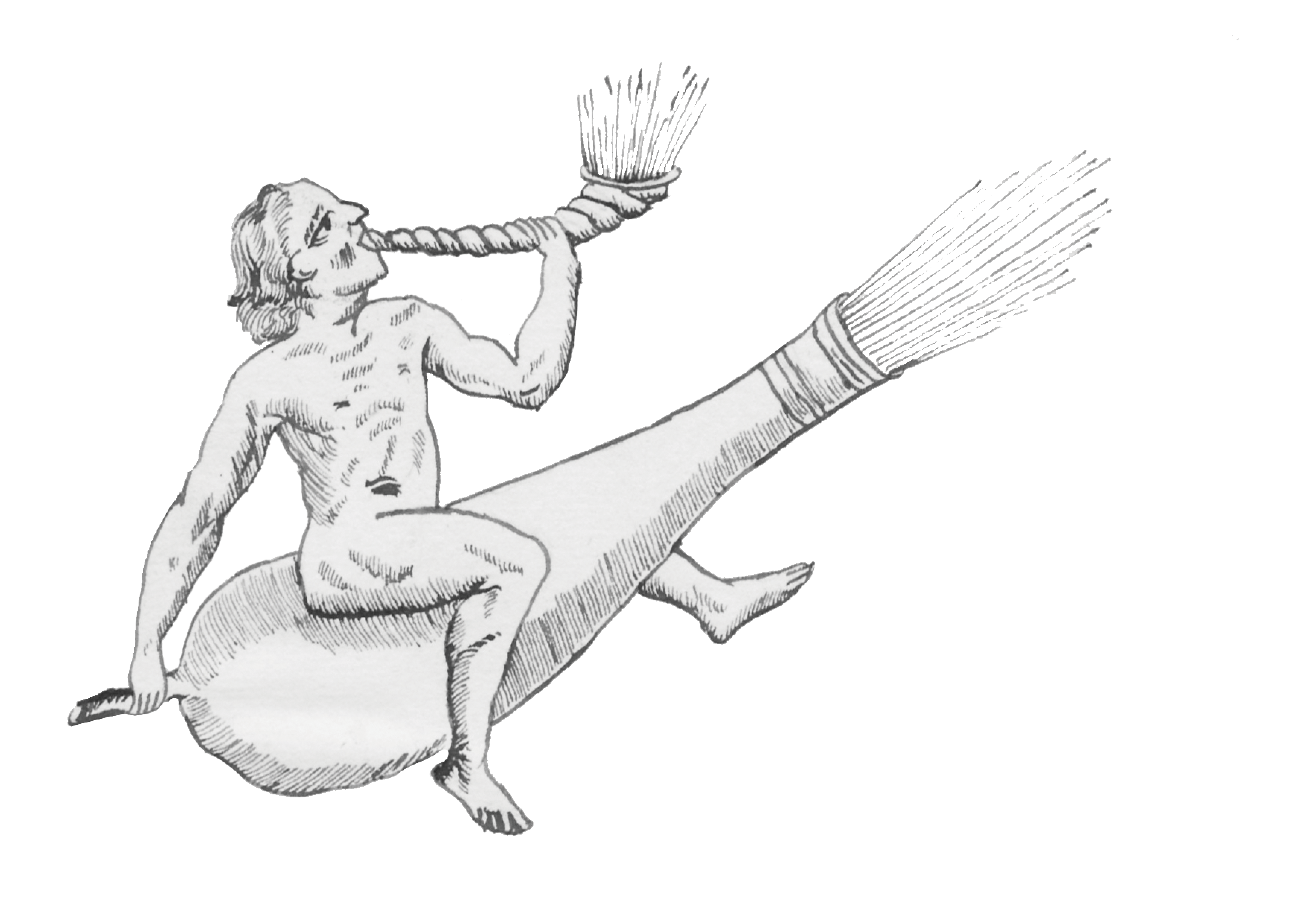

At the end of cartography atlas owned by Joachim Lelewel is a coloured drawing. It might be that these two characters were drawn by Lelewel himself.

When looking through the pages of the digitised atlas, you will see the drawing, as well!

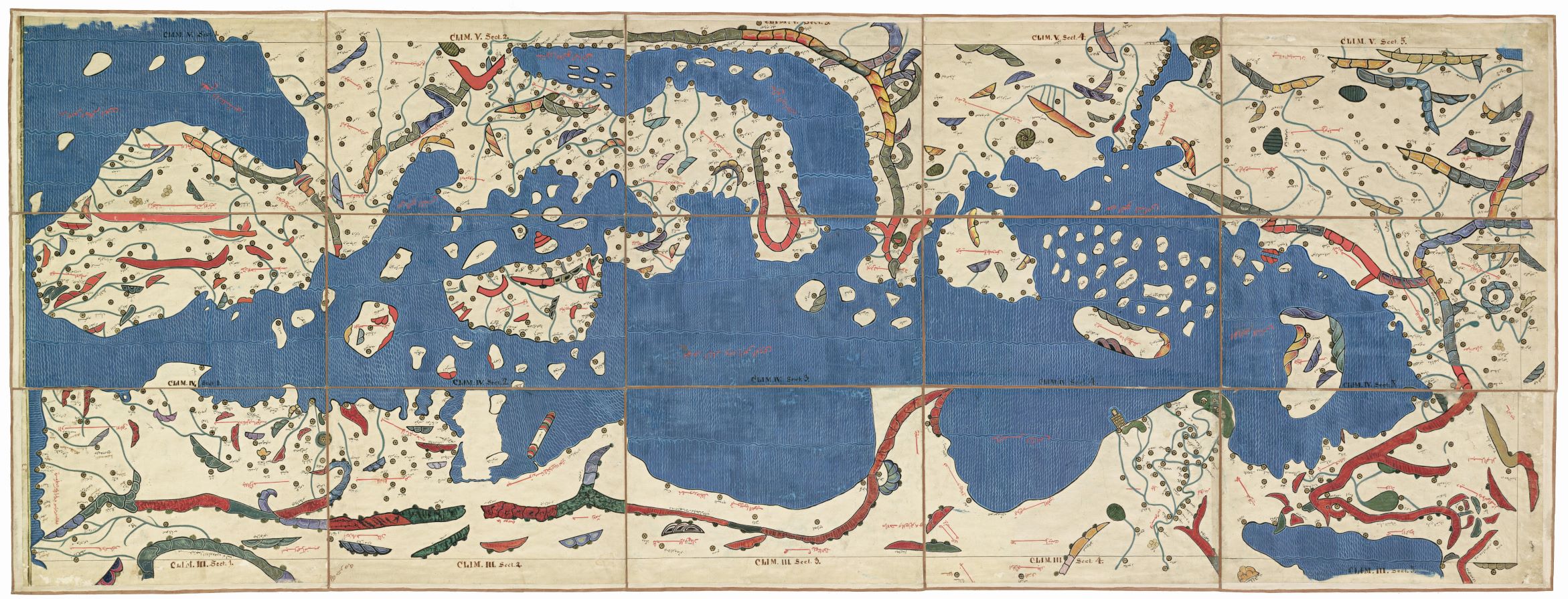

An Arabic Climate Map of the Mediterranean Basin. A manuscript copy by Joachim Lelewel (19th c.). The original is kept at the National Library in Paris.

The work of the most distinguished Arab traveller, geographer and cartographer Muhammad Al-Idrīsī The Excursion of One Who is Eager to Traverse the Regions of the World, commonly known as the Book of Roger (Tabula Rogeriana), was at the time the heyday of geography. It is the largest and most detailed geographical work of the 12th century that integrated both the Islamic atlas and the Greek Ptolemy's tradition and was based on the most accurate data of the time.

Commissioned by King Roger of Sicily, Al-Idrīsī prepared a detailed cartographic image of the then world, which was engraved on silver plates, and supplied it with exhaustive commentaries. He worked on this treatise and maps for 15 years from 1138 to 1154. For three centuries it had been the most accurate map of the world.

The work is written in Arabic; the Earth is divided into seven climate zones according to Ptolemy's system, each of which is subdivided into ten sections. It contains both the world map with Eurasia and Africa (only contrary to our usual orientation – with South being at the top and North being at the bottom) and maps of separate parts of the world. Later researchers of this work reconstructed comprehensive cartographic layout. Joachim Lelewel copied the majority of maps at the National Library in Paris (where the manuscript of Tabula Rogeriana is kept to the present day) and made his own layouts. One of them is An Arabic Climate Map of the Mediterranean Basin, which consists of 15 parts.

Information about Northern Europe and the Baltic nations is not exhaustive. Lithuania is not mentioned in the map. While describing Poland (Bulunia), Al-Idrīsī writes about prosperous city Madsun, the inhabitants of which venerated fire. It is thought that Madsun was situated in the territory of Lithuania.

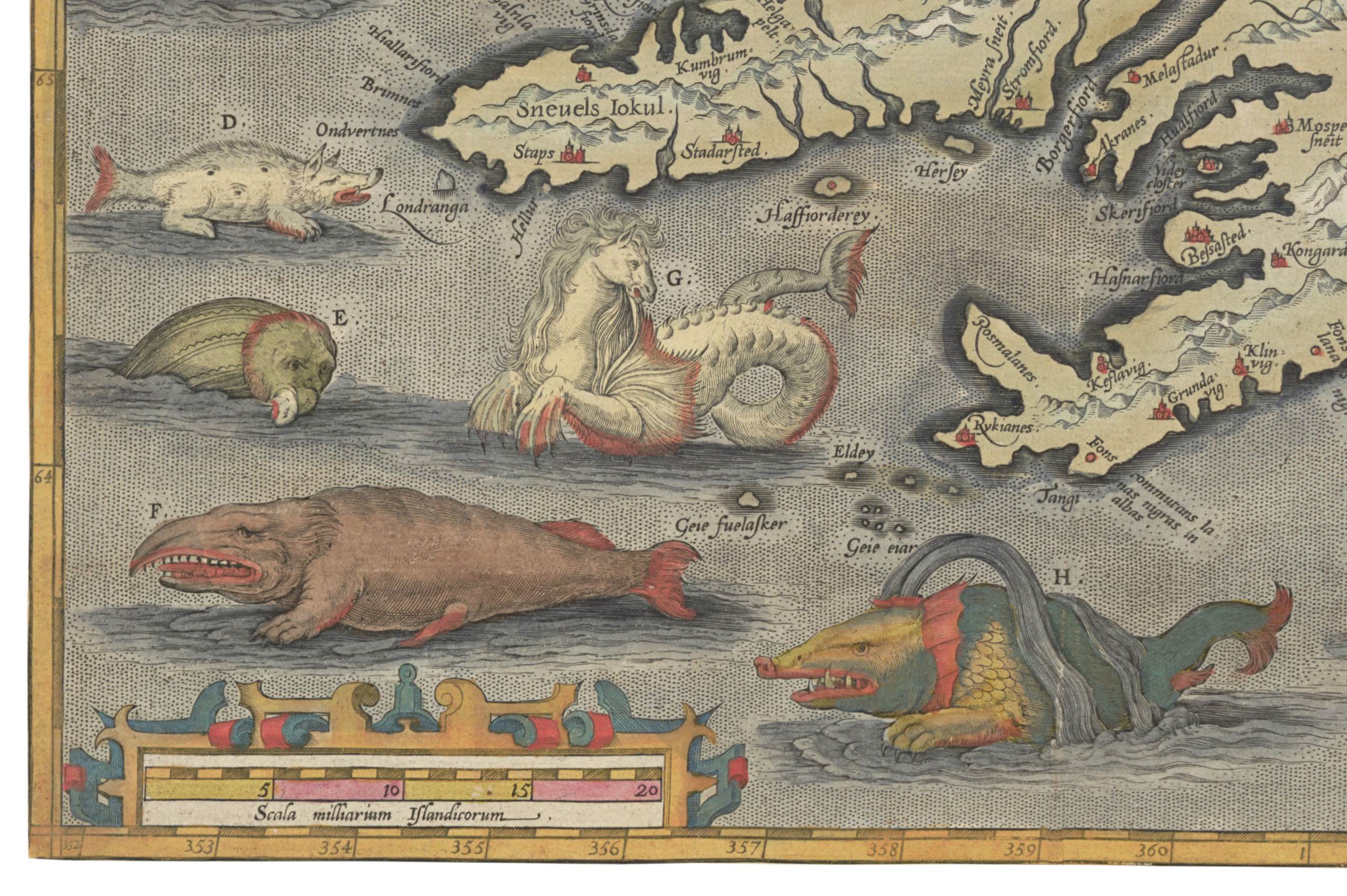

Map of Iceland from the atlas Theatrum orbis terrarum (Theatre of the World) by Abraham Ortelius. French edition, Antwerp, 1598. View atlas >>

Even now in Joachim Lelewel’s meticulously collected private library, covering a wide range of eminent names, treatises and cartographic pieces, one might open the atlas Theatrum orbis terrarum (Theatre of the World) by Abraham Ortelius, a Flemish cartographer, engraver and book and antique dealer. Lelewel had at least ten copies of this exceptional “mapbook” in his library.

The geographic atlas Theatrum orbis terrarum (Theatre of the World), considered to be a predecessor of modern maps, was published by Ortelius in Antwerp in 1570. It was Theatrum orbis terrarium that brought him success and prominence – the atlas was so popular that it had more than thirty editions and around seven thousand and three hundred copies in various languages in total.

In the later editions of Theatrum orbis terrarium Ortelius included a decorative 16th century map of Iceland, in which he depicted known-at-the-time settlements as well as mountains, glaciers, fiords, islands and bays. The engraving of the map records eruption of Hekla volcano and polar bears wandering on ice floes on the north-east coast. However, the largest amount of living creatures the author of the map placed in waters surrounding Iceland – here are situated images of sea animals and monsters that are engraved on a copper plate.

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, sea monsters appeared on maps for different reasons. On one hand, these minacious and bewitching creatures would make a cartographic work more splendid – decorative, playful and eye-catching images of monsters would increase the value of the map. Chimerical aquatic creatures were often depicted taking into account the idea that every land creature has its equivalent in the sea and thus the sea lion, the sea pig and the sea horse appear on maps quite often. On the other hand, some creators of maps aimed at conveying the then-knowledge of scholarly interest about yet unknown aquatic creatures.

Images of sea monsters often travelled from one map to the other. Chet Van Duzer, a researcher of nautical cartography, says that chimerical creatures came to Ortelius’s atlas from Olaus Magnus Carta marina et descriptio septemtrionalium terrarium ac mirabilium (Nautical Chart and Description of the Northern Lands and Wonders, Venice, 1539.). Waters of the Norther seas depicted in the map of this Swedish clergyman are thickly populated with various sea creatures and monsters. According to Chet Van Duzer, these are “the most important and influential sea monsters on a Renaissance map”, as Magnus’s works had made an enormous impact on cartographers who worked after him. Both the sea pig and whales as well as white bears moved from Magnus’ to Ortelius’ map. Descriptions of sea monsters, however, that are presented by Ortelius next to the map of Iceland, came from the other source. The creatures are described while using one chapter from Konungs skuggsjá (King’s Mirror, 13th century) written in Old Norse. According to Van Duzer, an interesting thing is that the book was not published until the 19th century, therefore it might be that information about the sea monsters came to Ortelius together with the map made by the Icelander Guðbrandur Þorláksson, which he used as a model. This plenitude of references and sources, and a complex maze of them is actually one of the features that make the Theatrum orbis terrarium so valuable – Ortelius used many cartographic and geographic sources for the improvement of his maps.

In a fragment of Ortelius’s map of Iceland, showing the Southwest coast of Iceland that is surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean, the following creatures appear on the map: a monstrous kind of fish that is called the hyena, or sea hog (D.), a horrible sea monster (Ziphius) swallowing a seal (E.), the toothless British whale – in the French edition of the atlas entitled baleine Britannique – whose tongue alone is seven ells in length (F.), a sea horse (or a horse-whale) – Horshvalur – that often causes great hurt and scare to fishermen (G.) and the largest kind of whale, which seldom shows itself and is more island than fish (H.).

Eventually sea monsters disappeared from the maps entirely – they gave way to more familiar marine and ocean creatures and an ever-increasing number of ships sailing on trade and other sea routes.

Fragment of a copper engraving by unknown artist portraying an allegorical scene. 18th century. Engraving from Žibuntas Mikšys collection.

According to stories by his contemporaries, Joachim Lelewel was a very diligent and modest person who would spend all his savings on acquisition of atlases and books. He also was a gifted artist, so when it was impossible to acquire some atlases or maps, he would copy them. In its stores, VU Library keeps Lelewel’s paintbrushes, colours and carbon paper used for copying. It is said that the professor would spend his money solely on books, milk and bread. Lelewel needed lots of bread as he would feed it to mice in order to protect his precious collection from destruction.

Joachim Lelewel Hall at Vilnius University Library. 2020.

In memory of Joachim Lelewel, one of the most spectacular halls of the university library was named after the distinguished scholar himself. While he was studying in Vilnius University, Lelewel learned how to draw here, in this exact hall. Lelewel’s drawing teacher was Jan Rustem, the most prominent Vilnius artist of the second half of the 19th century and a professor of the Drawing and Painting Department at Vilnius University.

The historian Joachim Lelewel held Professor Ernst Groddeck in high regard, who encouraged the former to take part in scholarly activities. Groddeck thought highly of Lelewel's talent and diligence and loved passing time with him.

During summers, in taking care of his daughters' health, Ernst Groddeck would move to Verkiai, a suburb of Vilnius, where he often used to invite Joachim Lelewel to stay with his family. Once while leaving Verkiai and invited for the dinner on the following day, the famous historian courteously asked the hostess Maria Groddeck if he could be of assistance and bring some necessities from Vilnius. The hostess asked him to bring some butter from their home as she was afraid that they will run out of it soon in Verkiai. The next day Lelewel sent his servant to do this errand. Groddeck's housekeeper decided to take the chance and sent an entire barrel of butter. Lelewel did not notice that the day was quite warm, and the passengers left for Verkiai in the noon, at the peak of sunshine. Lelewel, deep in his thoughts, and the carriage driver whose main concern was to lead his horse through a sandy and boggy path, did not pay attention to the butter melting and leaking through the barrel. When the carriage reached Verkiai, they had delivered only half of the barrel to the hostess. Groddeck's wife Maria was very unhappy about the incident, but her husband only laughed at her choice to give such task to a scholar – whereas Lelewel saw for himself once more that he'd better avoid all matters related to household.

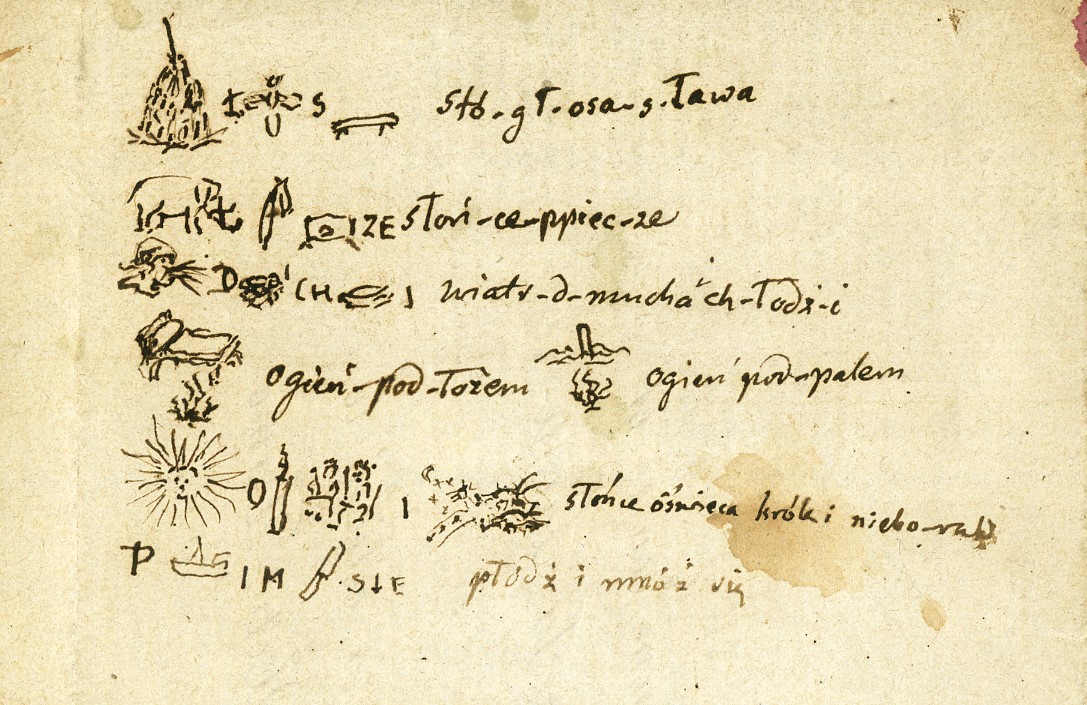

Joachim Lelewel’s archive contains a small piece of paper – a fragment of an invitation to visit Notre-Dame de Paris – bearing a charade created by the scholar (19th century) that has survived to the present day. Drawings of the charade contain a coded message in the Polish language that has not been decoded yet.

Joachim Lelewel’s archive contains a small piece of paper – a fragment of an invitation to visit Notre-Dame de Paris – bearing a charade created by the scholar (19th century) that has survived to the present day. Drawings of the charade contain a coded message in the Polish language that has not been decoded yet.

We hope that you make some exciting discoveries! >>

References: A text compilation Ortelius Atlas >> by Frans Koks; Chet Van Duzer, Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps, London: The British Library, 2013; Bibliographic information at Stanford Libraries >>

Illustrations from VU Library archives.