The coffers of Vilnius University Library hold many valuable documents that interest researchers of Lithuania and the world. One of them – a manuscript of memoirs written by Joseph Frank, an eminent professor of medicine of the 19th century who worked at Vilnius University – has been recently digitised and uploaded to the Digital Collections. The surviving five volumes of the memoirs contain a daily record of professor’s life and work not only in Vilnius, but also in Italy and Austria. The Franks, father and son, were well-known and held in high regard in Europe. They were acquainted with many famous people of the time; therefore, the memoirs spark an interest not only among the Lithuanian public. Giovanni Galli, a writer and translator from Milan, became interested in the memoirs some twenty years ago. He has already translated four volumes of memoirs that are originally written in French to the Italian language and the last fifth volume will be published in a short while. So, Vilnius University Library decided to interview Giovanni Galli so as to find out what led him to get involved in this, how it went, what were the most interesting and difficult parts, what new things has he discovered while translating the memoirs and what, in his opinion, would interest the readers of the Italian translation of the memoirs the most.

Q: How did you “discover” Joseph Frank?

A: Well, I grew up in Como, and in a nearby village on the shore of the lake there is an imposing pyramid that I admired every time I passed by the village biking or on a boat. When I retired, I decided to investigate the person whose remains are buried in the pyramid. This person was Joseph Frank and, over the years, I learned a lot about him by visiting libraries and archives, meeting people and traveling throughout Europe – including Vilnius, where I read Joseph Frank’s Memories. In the end, I published a biography of the Franks (La piramide di Laglio, or Laglio’s Pyramid, Laglio being the name of the village where Joseph Frank is buried). Having discovered Joseph Frank’s Memories, I decided to translate them.

Q: Between 2006 and 2010 you have translated Volumes I, II and VI of Frank’s Memories for the University of Pavia’s History Centre. Now, ten years later, you have translated the 3rd volume and published it with a different publishing house. Why?

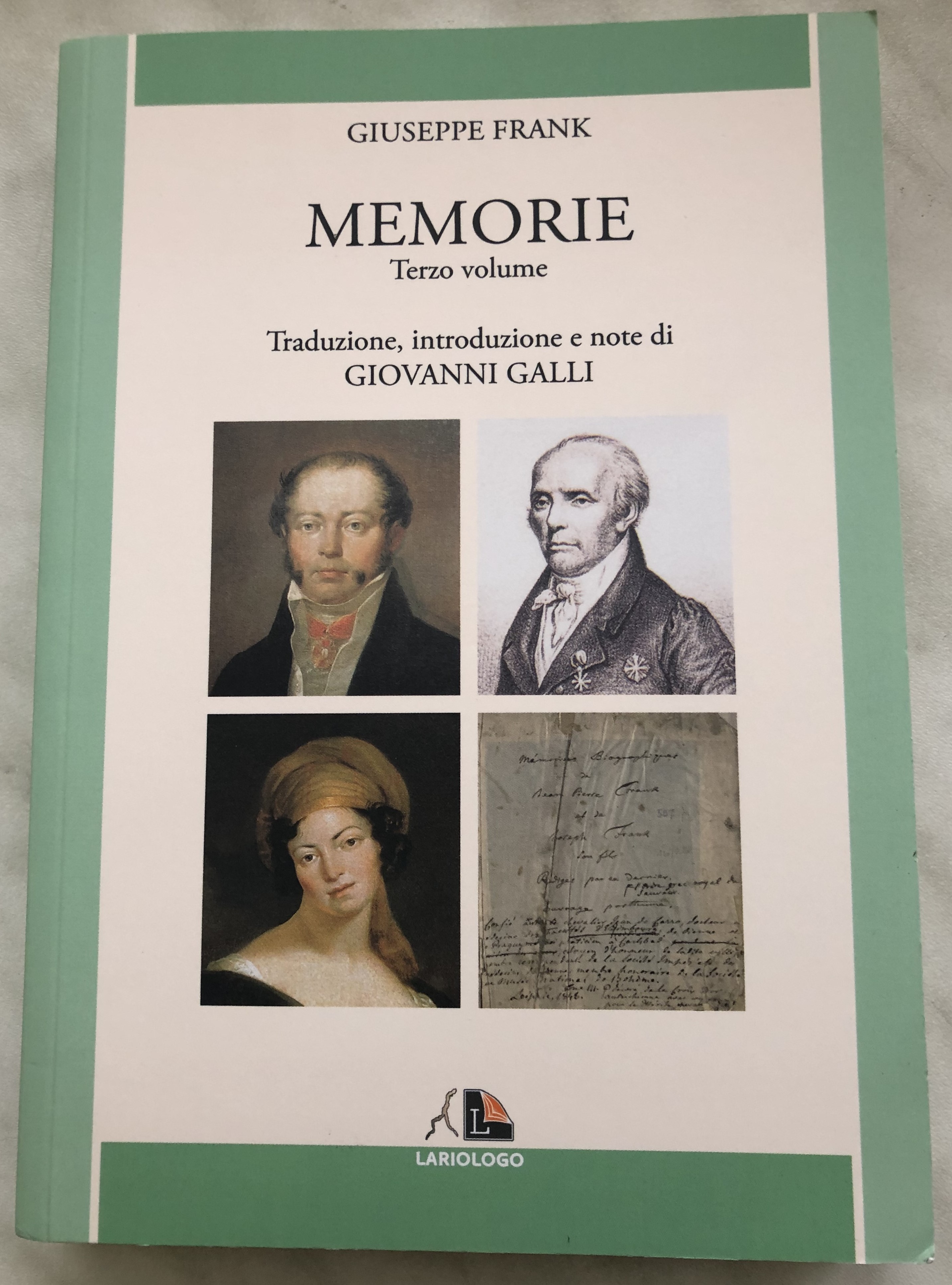

A: In fact, the Centre decided to publish the three volumes that you mention because they contain several references to the University of Pavia, where Johann Peter Frank taught, and his son Joseph studied between 1785 and 1796. Volume VI deals with Joseph Frank’s last years that he spent in Como where he died in 1842, whereas Volumes III and IV of Frank’s Memories deal with the years 1806 to 1823 that Joseph Frank spent primarily in Vilnius; thus, Pavia Centre showed no interest in publishing these two volumes. Seeing as last year we were confined at home for several months, I decided to take advantage of this voluntary imprisonment to complete the translation; but Pavia Centre showed no interest in printing it, either, and so I decided to publish the two remaining volumes at my own expense. Volume III has just been published and Volume IV will follow, hopefully, by the end of this year.

Q: Were there any new things, new discoveries for you when translating Volume III?

A: Not really. In fact, in 2002, a year before publishing La piramide di Laglio, I spent two weeks in Vilnius reading the manuscript of Memories; not all of it, of course, but a significant part, including Volume III. But, naturally, during the translation I discovered a lot of details I had disregarded when I read the manuscript in 2001. One of them is particularly interesting as it permits to discover an oft-forgotten aspect of Joseph Frank’s character. I refer to the episode mentioned at the beginning of Chapter 59, concerning a new-born baby abandoned at the entrance of Frank’s house. A foundling, writes Frank; but thereafter he adds ‘somebody thought that I was the father’ and later continues, ‘but they were wrong’. My opinion is that they were not wrong, considering the fact that Joseph Frank has been a libertine since his youth, before and after the marriage, as he himself reports in several chapters of his Memories.

Q: In Lithuania the activities of father and son Franks were remembered during the pandemic, as they opened the Vaccine Institute in Vilnius. Were they remembered in Italy?

A: No, as far as I am aware, in Italy nobody recalled the Franks in connection with the pandemic. Probably due to the fact that while the massive inoculation of the vaccine against smallpox was initiated in Lithuania by Joseph Frank, who also opened the Vaccine Institute in Vilnius in 1808, the introduction of the vaccine in Italy was thanks to doctor Luigi Sacco, after whom we named the most important Milan Infectious Diseases Hospital.

Q: What is peculiar to Frank’s style of writing?

A: Well, if the question refers to his calligraphy, there is not much to say: it is plain and leaves little doubts as to the transcription. The only thing that occurs to my mind is the use of the letter “W” instead of the letter “V” in proper nouns – for example, in Wilna. This can be explained by the fact that in German the letter “V” has an f sound, while the sound v is written as “W”. Joseph Frank submitted his manuscript to a friend of his, Doctor Jean De Carro, to make sure that his use of the French language was correct, and Doctor De Carro corrected Wilna in Vilna. The same thing happened with many Russian names ending in “ov”; Frank transcribed those as “off”.

If the question refers to the syntax instead, I must confess that it is very tortuous, with an excessive use of gerunds that forced me to modify somewhat the turning of the phrases in order to make them clear to the modern reader.

Finally, if the question refers to the use of the French language, we must remember that in the first half of the 19th century the French language was the lingua franca, as it is the English language today; if Frank had written his Memories in his native language – German – few people would have been capable to read them outside of Germany and Austria.

Q: Do you think there are more documents connected to the Franks that were not found yet, maybe letters or other memoirs?

A: As to Johann Peter Frank, this question should be put to Johann Peter Frank Society in Rodalben; I visited their seat of residence and spoke with some of the members, but as I do not speak German, I could not read the papers they have in their archives.

As to Joseph Frank, the only place where letters or other materials could be found is the University Library of Pavia; in fact, when he died, all his papers and books were donated to the University of Pavia and are still there.

Q: Now that they are part of the library homepage and open to everybody, will Memories attract more attention?

A: Hopefully yes, although being somewhat old-fashioned, I continue to prefer paper books instead of electronic books.

Q: Do you think Memories should be published in other languages?

A: So far, to the best of my knowledge, Memories have been published in Lithuanian (Chapters 50 to 75), in Polish (all volumes, at different times) and in Italian (Volumes I, II, III, and VI; Volume IV will follow soon). Ideally, it would be useful to print Memories in French, their original language, but the point is that they deal principally with events concerning Austria, Italy, Lithuania, Poland and Russia, so it is difficult to find a French publishing house disposed to invest the necessary amount of money. Maybe somebody could consider publishing a German version, but as far as I know nobody has ever shown an active interest to this end. As to an English version, it would be useful, but the same point above applies here, as well.

The story on how Joseph Frank’s memoirs happened to appear in our library is really intriguing. The original is written by the hand of Joseph Frank himself between the years 1830 and 1840. While the professor stayed in Carlsbad, the memoirs were edited and revised by his close friend and Swiss-born physician Jean de Carro. After Frank’s death in 1842, his widow Christine Gerhardi contacted Jean de Carro and asked him if he could take on a responsibility to publish the memoirs. De Carro intended to abridge 6 volumes into two, as he deemed the book to be too large. After the death of Frank’s widow, the physician sold the memoirs to the Polish duke Reynold Tyzenhauz, who gave them to Vilnius Medical Society. The 5th volume disappeared due to unknown reasons. It might be that this volume that was written after Frank left Vilnius contained many commentaries on Vilnius University, the November Uprising and specifically the Russian influence. It could be that it was decided to destroy the book so as to avoid problems with the Tzarist authorities. We are proud in such an interesting document being kept in VU library.

An impressive gravestone to the eminent professor – the pyramid by the Lake Como – was created by Joseph Frank himself. It is 20 meters high and 13 meters wide. The professor bequeathed in his testament 25 thousand Swiss francs for the construction of the pyramid. By the way, Giovanni Galli became interested in the memoirs and Vilnius after he undertook some effort to find out who built this impressive pyramid. As he himself told us, he looked through the Joseph Frank’s testament in the municipality of Como. He found as many as 77 detailed instructions left by the professor on how to build the pyramid as well as its sketches.

Nijolė Bulotaitė

2021-07-02